I thrill when I drill a bicuspid.

It’s swell, though they tell me I’m maladjusted…

But somewhere, heaven above me,

I know,

I know that my Momma’s proud of me.

Excerpted from the song “Dentist!” from Little Shop of Horrors

Steve Martin was the first comedian I grew to love as a kid. I usually tell people it was George Carlin (R.I.P.), but I didn’t really get into Carlin until I was a teenager and my appreciation of Martin began before that. If I was being completely honest I would say the first was actually Robin Williams (R.I.P.), but Williams was so omnipresent throughout my childhood I can’t actually remember a time when I didn’t know who he was. So that doesn’t really feel right, either. No, the first comedian I gravitated to of my own free will was the white suit-wearing, banjo-playing dork with the white hair and the glib smirk. The one who gave the world “air quotes”, yelled, “WELL, EXCUUUUUUUSE MEEEEEEEE!”, and whose breakout movie role was playing a man so dumb he doesn’t know he’s white. I had two of Martin’s standup albums on CD, and I played them both over and over again. If you get enough beers into me, I might even remember most of the words to the King Tut song.

Like a lot of standup from the 70s and early 80s, the routines on those albums are pretty quaint by modern standards. The most shocking one I can still remember starts with Martin milking the audience for kindness over the recent death of his girlfriend, only for the story to climax with Martin revealing the reason she’s dead is he murdered her with a shotgun; “blew her right in half!” Despite the premise, the routine feels almost charming in its restraint in a post-South Park, post-Family Guy, post-4chanification-of-culture world. There’s no swearing, no histrionics, no shouting or yelling or overt misogyny in the tone or delivery. It’s the most basic kind of humorous misdirection: Martin fools the audience into giving him sympathy with a sob story about a dead loved one, only to pull the rug out from under them and reveal he’s been playing them like his personal banjo collection. The simplicity of it, and the confidence Martin displays pulling it off without needing to make the joke “edgy” or hateful, is why the routine still works decades later when a more overtly shocking or offensive version would probably feel stale.

It was thinking about this joke, specifically the way Martin delivers it, that made me realize what it was that made his humor so attractive to me as a young, deep-in-the-closet trans girl. It wasn’t just that he was obviously smart and didn’t try to hide it, which appealed to the nerd in me. The singing and dancing certainly appealed, too; that the dancing was hilariously bad appealed even more. But the true hidden appeal of Martin’s comic persona was the way he purposely took on exaggerated versions of traditionally masculine personality traits — blustery confidence, self-impressed ignorance, bragging about how big your pyramid is — and held them up for scrutiny in a way where you couldn’t ignore how flimsy the pretense is that these are worthwhile or admirable qualities. All of Martin’s most famous characters have that campy affectation in one form or another, from the disastrously ignorant and self-absorbed main character in The Jerk to the tourist trap huckster of “King Tut.”

Thankfully, jokes about killing women with shotguns are an exception in Martin’s work, which tends to rely more on a keen sense of irony than shock or disgust. But there is at least one glaring exception from his long career as a comic actor. Instead of satirizing overblown male confidence and self-regard by holding it up for good-natured mockery, for this role Martin took his self-aware embodiment of faulty masculine qualities to its logical extreme. That would be his performance as Orin Scrivello, the abusive, sadistic, Elvis-impersonating dentist from 1986’s Little Shop of Horrors.

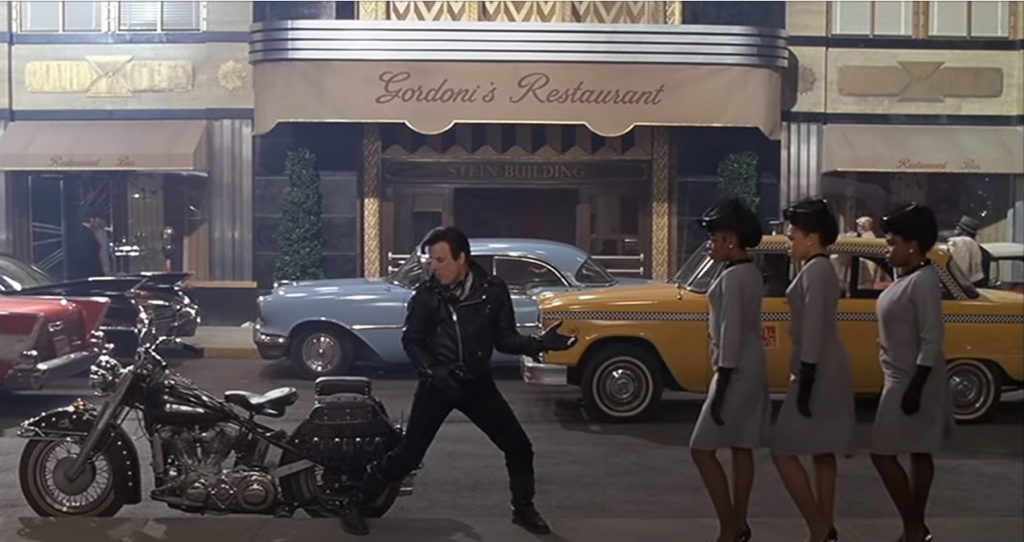

Everything about Scrivello screams, “masculine.” The black leather jacket, the motorcycle, the overconfidence, the condescending sneer, the exaggerated Elvisisms. Scrivello is also the only character aside from the chorus to conspicuously break the fourth wall; whenever he does, Scrivello mugs for the camera with the obvious belief that the audience has to be impressed with him. When Scrivello is introduced, he’s right in the center of the frame, dominating the entire screen and sneering right at the camera, projecting both indifference and menace at the same time. Scrivello also has the only character song told entirely from the perspective of a narrator recounting his own backstory. Even Little Shop‘s main characters Seymour and Audrey seem unaware of the audience at any time, even when they’re singing about themselves, but Scrivello is introduced looking the audience right in the eye with a condescending sneer. Scrivello’s bullying extends to the diegetic world Little Shop‘s main story takes place in, too. As soon as Scrivello enters the waiting room of his office, he is already terrorizing his patients and employees, utterly confident it is his right to gain pleasure from their pain. The menace he embodies is palpable as he prowls through the office, teeth bared in a menacing snarl at a lobby full of cowering people waiting their turn to be tortured at his hands. Even as obviously exaggerated as Martin’s performance is, Scrivello is still terrifying; or he would be, if he didn’t look so silly every time he tries to bully the audience.

Underneath the outward aggression, Martin is still doing his usual schtick. What makes the performance so notable, and what makes Martin’s self-aware embrace of campy masculinity such an important part of its makeup, is how little about Martin’s on-camera persona needed to change for him to convincingly morph from good-natured, dad-joking blowhard to the living embodiment of abusive male rage and entitlement. It’s the same trick Robin Williams used when he would play a dramatic role by slightly recalibrating his usual comedic delivery in a way that made everything he said feel shockingly sincere, completely different from his comedic persona but still eerily similar enough that it was impossible not to notice.

It’s easy to imagine Martin playing a serious version of the role and doing an extremely good job of it. His comedic take on the character demonstrates he understands the mess of anxieties, fears, and fetishes that make up a man like Scrivello. Scrivello is cocky and entitled, but his hold over people is based entirely on fear and pain; to maintain his ego, Scrivello has to constantly project an image of strength and dominance over everyone around him. When one of Scrivello’s patient displays a masochistic enjoyment of the pain Scrivello inflicts on him, the usually confident dentist loses his cool at the loss of control. He acts like he doesn’t care what other people think, but the amount of effort he puts into flexing on everyone he meets proves he’s obsessed with how the world sees him. Scrivello may have fooled himself into thinking he shares a kinship with The King’s rock n’ roll rebel image, but aside from a bad attitude there’s nothing rebellious about him: a successful dentist and straight white cis male business owner in 1950’s America, a man so used to getting his way he is free to terrorize and abuse everyone he meets without consequence. Scrivello is so used to having the world cater to his whims the only way he knows how to react to someone disobeying his wishes is to beat them.

And somehow, Martin’s performs the role in a way that makes Scrivello both hilarious as well as frightening, impossible to take seriously as a person but still an ever-looming danger to everyone around him. Scrivello is pathetic in every way that matters, but he’s also a paragon of the virtues society idolizes as the peak of masculinity.

In other words, a Steve Martin character.

One thought on “The Campy Masculinity of Steve Martin”